Thanks to Jared Hunter for his latest, a look at how the Economic Opportunity Act stacks up against the best practices of local tax policy.

I am currently taking a public budgeting and finance course at Rutgers Camden and while this topic doesn’t usually gather a massively engaged crowd, I find the content compelling, especially when applying it through a Camden lens. One of the texts that we are reading in class, Local Tax Policy by David Brunori, gives a detailed outline of grasping the fundamental principles of local tax policies. In one of the chapters, the author delves into what a sound tax policy looks like both in theory and practice. For those who have been keeping a closer eye to the booming economic development in Camden in the last few years, the five basic principles of a sound tax policy can very quickly be analyzed through this lens. The result of this increased economic development in the city is a direct correlation to the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA), and I’ll get deeper into that in a little bit.

The five basic principles of any sound tax policy are as follows:

- Adequate revenue sources; this principle is grounded in a basic need to understand exactly how much tax revenue is being collected and ensuring that there are enough places to collect this revenue from.

- Equity; this principle breaks down into two components: a) horizontal equity which means that everyone who can pay taxes should pay taxes, and b) vertical equity meaning that those who can pay more taxes should pay more taxes.

- Neutrality dictates that tax policies shouldn’t influence any economic markets.

- Ease of administration and compliance; this simply accounts for a tax code that is both simple to understand and fulfill

- Accountability; this principle calls for legal procurement of resources needed to provide public goods and services, strong and dependable enforcement of the tax policies, as well as an openness and transparency between tax payer and payee.

Now I want to start this off with a disclaimer that while the EOA is not primarily a tax policy, it does exemplify taxation through required action and reaction from taxpayers following a similar flow. As we look deeper into neutrality, we see that as the EOA affects the economic markets of the state, taxes are also distorted and are inevitably shoved off to the everyday taxpayer.

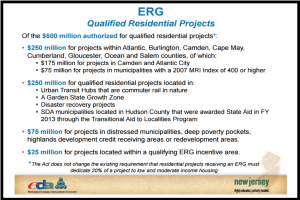

Understanding these five basic principles of sound tax policy, and now applying this specifically to Camden, we can see a large disconnect between the tax policies in our city versus policies that create equitable and sustainable economic development. Administered by the state’s Economic Development Authority (EDA), when boiled down to its essence the EOA provides tax breaks/incentives and tax credits to businesses that create and retain jobs in New Jersey, specifically in the eight southernmost counties (Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, Ocean, and Atlantic). All of this incentivized economic development is implemented through subset programs like the Grow New Jersey Assistance Program (Grow NJ) to reward job creation and the Economic Redevelopment and Growth Program (ERG), the bill’s developer incentive program.1 Additional benefits are up for grabs for businesses or developers operating inside Garden State Growth Zones, designated to the four poorest cities in the state (Camden, Trenton, Paterson, and Passaic) based on median family income.2 In 2015, the household median income in Camden was $25,643 compared to the state average of $72,222 – there’s also an interesting from DataUSA that gives the median age of the Camden city population as 28.9 years old with the population of citizens between 25 – 34 years old accounting for the highest rate of poverty (we can look closer into this in another post).3

Let’s look at the first principle of adequacy or revenue sources. When the EOA was passed in the New Jersey State Legislature in 2013, the premise of the bill was essentially to attract, create, and retain jobs in New Jersey through substantial tax breaks, credits, and other incentives. This is an amazingly altruistic purpose in theory and on paper as employment in New Jersey at the time was still badly crippled by the Great Recession and still just trying to get a mental grasp of the work ahead after Hurricane Sandy hit the year before. Still, based on this principle, with new developments coming into the state that won’t be contributing to the tax base, New Jersey has reduced its adequacy of revenue sources and failed this component of a sound tax policy.

With a decreased tax base (i.e. less contribution to the total taxable amount of money in the city), the ultimate question that remains: these new developers are coming into Camden and not paying taxes, so who’s going to picking up the tab? Since recent developments began, many community members I’ve spoken with have told me that their taxes and property values have both increased; this is understandable because property values are intrinsically tied to property taxes. And even though the EOA stipulates that the businesses and developers coming to the state have a limited amount of time to take advantage of these incentives and breaks (most of them are a minimum of ten years), who’s to say that when the credits dry up they will stick around and begin paying taxes rather than leaving the state or threatening to leave unless they receive more tax credits? We know that the principle of horizontal equity dictates all those who can pay taxes should pay taxes and vertical equity dictates that all of those who can pay more taxes (based on a higher income) should pay more taxes; the EOA bill flows against this component of a sound policy and therefore, once again, misses the mark.

Taxes that affect economic markets are not neutral policies. The EOA promotes economic inequalities throughout the state, essentially changing the taxation landscape of New Jersey. While the EOA presents a much more attractive landscape to businesses, corporations, and developers, those respective markets have been accommodated to simply get them through the door while small businesses and individual taxpayers have fewer options to take advantage of such opportunities this bill promises. This is not neutrality.

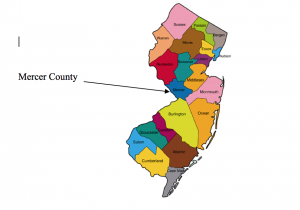

Openness and transparency within a tax policy – and really any policy approved by a government legislature – is the strongest key in creating solidarity between tax enforcers and payers. Being aware of a policy and its effects on the everyday individual under submission to that law is without question necessary for its ease of administration and compliance. I took an extremely quick-and-dirty survey of my coworkers and asked them all one simple question: Do you know what the Economic Opportunity Act is? Out of the thirty-three people I asked, only one person truly understood what the law was – one coworker knew that the EOA was state legislation though wasn’t entirely sure what it entailed so we’ll call that a half. If this is any indication of the transparency and openness of the EOA, then only 4% or about 350,000 New Jersey citizens (just shy of the total population of Mercer County) know what this bill is and how it could affect their everyday taxpaying lives.

It’s important to realize that this information, while not completely validated in thorough analytic research, truly does exist and provides a clearer view of the current economic landscape of our state. Yes, we were facing many hardships both economically and naturally, and legislators took the actions they felt the most appropriate at the time to address these hardships; and for this I commend their expediency in attending to such a devastating moment in our state’s history to put politics aside and get people back to work. But what does it say about those representing our interests when the short-term gain and long-term pain is the true scenario in which they place future generations?

Long story short, the state was losing its bearings in almost every facet of public life and legislators knew something needed to be done as soon as possible. Unfortunately, the result – perhaps partially borne out of the fact that we were so beat up and had very few options to leverage resources intentionally and equitably – has shown itself as a much longer term issue that current and future administrators are still unsure exactly how to revamp. The best option for the state is to truly review the current structure of accountability, transparency, and “length of stay” for the incentives presented through this legislation. New Jersey leaders need to understand that short-term pain and long-term gain can exist just as easily with those willing to truly change the state’s viability rather than that of their public office.

Jared Hunter is a current student at Rutgers-Camden pursuing his Masters in Public Administration in the community development track. His research focus includes disparities between marginalized communities and local governments as well as community development centers and anchor institutions.

References:

1)https://www.njeda.com/getattachment/Press-Room/resources/Summary-of-New-Jersey-Economic-Opportunity-Act-of/NJEconomicActof2013_summary.pdf.aspx

2)https://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/x/273494/tax+authorities/New+Jersey+Enacts+Economic+Opportunity+Act+of+2013

3)https://datausa.io/profile/geo/camden-nj/