Thanks to Camden resident Jared Hunter for this guest post. Jared lives and works in the city, and is a graduate student at Rutgers-Camden.

I grew up in the boondocks of southern Gloucester County; my father worked and my mother was a homemaker; there were seven of us crammed into an extremely tiny three-bedroom apartment for over a decade; I shared a twin sized bed with my brother (who is only one year younger than me) until I was nine years old. As a result, my mother quickly and forcefully began to learns the ins, out, nooks, and crannies of every possible public outlet to utilize supporting our family the opportunity to survive. There were many road trips from Williamstown to the Board of Social Services building on Holly Dell Drive in Washington Township. She learned that our local government had more to offer our family for food stamps, clothing, after school activities and anything else a weighed down, poverty line toeing mother of five would need.

But in Camden I don’t see that connection as much; in fact, it seems reversed insofar as that the community is performing much of the people-focused work of the city. Investing in people as much as buildings is another key component of a sound local government, though I will dive deeper into this concept in another post.

I started my research with Rutgers Camden last semester and it took off at the start of this year. I wanted to better understand the upbringing that I experienced in more deeply examining how a marginalized community (i.e. one found on the outskirts of the main “hustle and bustle” of a city) and its members interact with the local governments that represent those communities. Many times, in instances of larger urban and metropolitan areas (e.g. Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, Los Angeles, etc.) we see that there is a concentrated area in which the city thrives and receives much of its political and economic substance. On the other hand, we see that those regional communities of the city can feel neglected due to lack of resources and participation in decisions that affect their daily lives. In Camden, we this is evident of recent economic development downtown like Holtec’s new campus in Waterfront South, Subaru in a juxtaposed corner between Lanning Square and Gateway, and of course the “eds and meds” corridor for Cooper University and Rutgers University downtown.

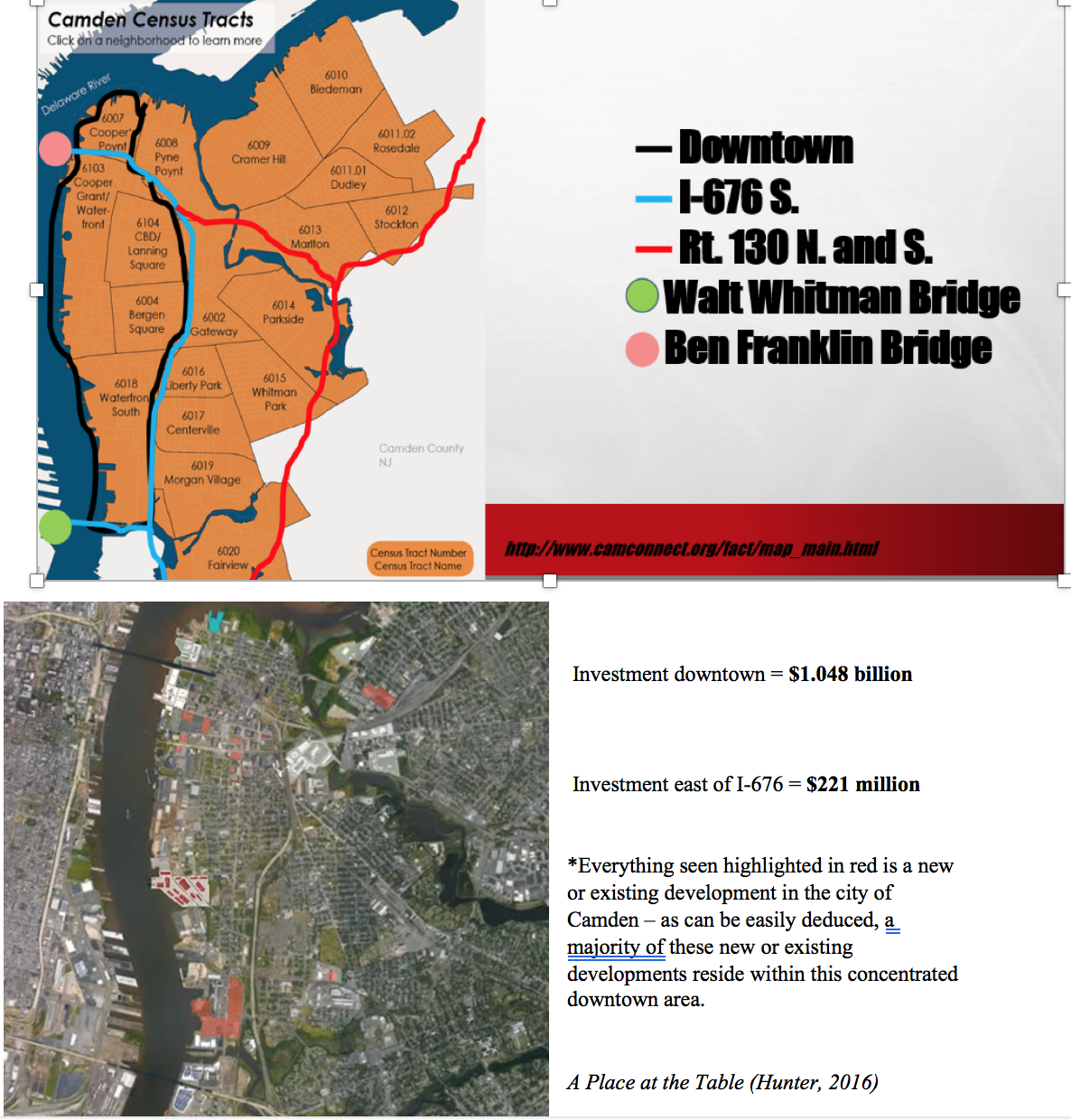

What wasn’t as easily clear until I actually began engaging with the city was that all this economic development is concentrated, squeezed into a tight-knit area of the city. If you look at map of Camden broken up into all of its diverse neighborhoods, you can see that of the total $1.25 billion displayed in the city’s Camden Rising video, close to $1.05 billion has been smooshed between the northern Ben Franklin Bridge, the southern Walt Whitman Bridge, the western Delaware River, and the eastern I-676 highway system. What you find on the eastern side of 676 is what I refer to as marginalized – literally.

So, after digging through as much as I could in my first semester, I really refined what exactly I was going to focus on in the fall and by January I had ten stakeholder interviews in two weeks. I sat down with local organizations, politicians, and community leaders representing Parkside Business and Community in Partnership (PBCIP), the Latin American Economic Development Authority (LAEDA), Camden Organized for Responsible Development (CORD), Camden Churches Organized for People – now Faith in New Jersey (CCOP), among many other stakeholders responsible for the regional landscape of the community-based work in the city of Camden. And from most of the community development organizations I spoke with – there was a resounding tone from the community of a lack of cooperation from city hall:

“The impact of the waterfront development isn’t seen in the rest of the neighborhoods.”

“You have upper echelon leaders never touching what the community is actually living in.”

“Even when we do communicate with [city hall] they don’t hear us.”

“CDC’s are doing the city’s job.”

With an overwhelming amount of state control, lack of trust in government, recent school closures, along with little to no tangible outcomes seen outside of a concentrated downtown, the community has presented an overwhelming sentiment: we don’t want a connection with local government right now, we need to hold them accountable. Right now Camden doesn’t need a relationship to alleviate its troubles with city hall, it needs a place at the table to ensure they can hold their leaders’ feet to the fire and create a more equitable environment for all of its citizens to thrive and not simply survive.

It was difficult enough for my mother to navigate the tumultuous waters of county and state bureaucracy and come out with even crumbs to satisfy the exorbitant needs of five children – one with Down Syndrome I might add. I can only imagine how much more difficult it is for everyday folks, people just like my family and the friends we grew up with together, scraping to get by. I say all of this to say that we were poor growing up and I can not only empathize with the folks in Camden dealing with tight quarters, dilapidated homes, and very little perspective of a brighter horizon just around the corner – I can reminisce with them. From these experiences, the city has managed to somehow move forward with grace and beauty and hope. And that’s just what I learned about leadership growing up like so many in Camden have and are, even right now: that when your back’s up against the wall and you’re pinned into a corner, you eventually always come out swinging; that’s what folks want to see, the guy (or girl) who’s got their back – a fighter in their corner.

I’m so proud rite Now! Jared Hunter is my grandson and I’m so thankful for him and his caring nature. God is on his side. Good things are going to happen because of him. Thank you Jared.